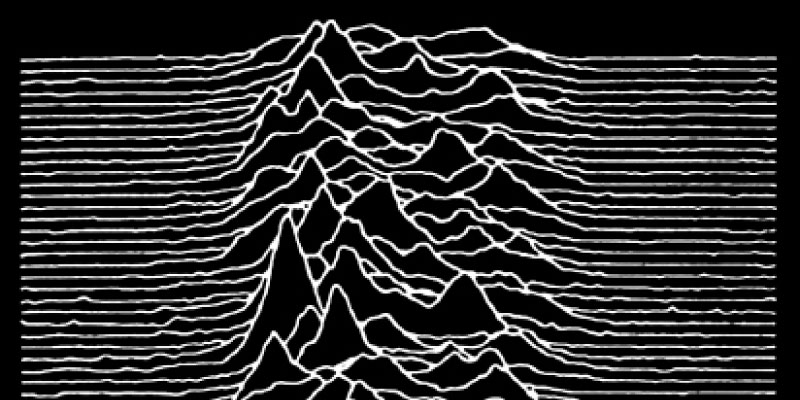

Few record covers have endured as long as that of Joy Division’s album Unknown Pleasures. There are T-shirts, posters, tattoos and art exhibitions

featuring the image – the fact that even Disney produces an image of Mickey Mouse based on the cover’s design is an indication of true greatness. However, the roots of the image go back to science.

By Nicklas Hägen

When, in 1979, the four members of the post-punk band Joy Division turned to the record company’s artist Peter Saville with an idea for the album cover, they probably based it on in- stinct. What exactly made the band’s drummer Stephen Morris pick up The Cambridge Encyclopaedia of Astronomy is unclear, but nevertheless there he found the image for a cover that has gone on to have a life of its own for over 30 years.

It is equally unclear what made Jocelyn Bell Burnell respond to the radio signals picked up by the observatory’s parabolic antennas in 1967. The discovery by the then post-graduate student gave her thesis supervisor the Nobel Prize in physics seven years later and it is depicted in the form of the curves on Joy Division’s album Unknown Pleasures.

“Radiation of various kinds is our only source of information about the universe, but we cannot respond to all the signals which are picked up by our instruments. First it was assumed that the signals came from a transmitter situated on the face of the Earth. So it’s important to keep one’s eyes open and not dismiss potentially interesting finds such as deviations in measurement data”, says Johan Lindén, a lecturer in physics at Åbo Akademi University.

The curves in the picture represent the signals from the first-ever discovered pulsar, which was initially nicknamed ‘LGM-1’ (‘Little Green Men’) because of its extraterrestrial origin. The first real name given to the pulsar was CP 1919, while today it is known as the PSR B1919+21. It is part of the constellation Vulpecula, commonly known as the Fox.

Tremendous pace

When a star is about to die, its pressure decreases rapidly, the star collapses under its own weight and a supernova is formed. During this process the outermost layer of material is hurled out into space, while the inner layers are compressed.

Depending on the size of the supernova, either a black hole is formed, if its mass is big enough, or a neutron star, if the mass is smaller. According to current theories, black holes are surrounded by a gravity field so strong that not even light emerges from it. The compression is weaker in neutron stars, but strong enough for electrons from the star’s atoms to have been forced into the core of the atom. These neutron stars can be smaller in size than the planets in our solar system, and they rotate around their own axis in a few seconds or less.

Neutron stars generate a magnetic field, which because of their fast rotation emanates energy in the form of radio pulses. If the radio waves radiate in a certain direction, they can be registered as highly regular pulses on Earth. Such neutron stars are called pulsars.

The pulsar PSR B1919+21 sends out a signal every 1.3373 seconds. “Several pulsars have been discovered and they are all equally dull, as compared to the radio pulses sent by broadcasting radio programmes. All they do is repeat themselves”, says Lindén.

“But they do have certain areas of use. Just as there are earthquakes, there are starquakes, too, and when one of these takes place, the radius of the star changes, which is reflected in the rhythm of the pulse. These can also be used for calibrating instruments, such as telemeters, and for finding out what there is in the almost total emptiness of space.”

Artistic impact

There is an entire field of aesthetics linked to science and the border between science and art. Étienne-Jules Marey and Ernst Mach were among the pioneers of the use of photography within science with their experiments on movement in the late 1800s.

The same period of time saw the birth of Modernism. Jenny Wiik, a doctoral student in art history at Åbo Akademi, says that the aesthetic roots of the cover of the Unknown Pleasures album reach back to the beginning of the 20th century.

“Abstract art developed during the second half of the 19th century, and, contrary to academic art, it did not aim at depicting a reality or an ideal. In the early 20th century Picasso and Braque developed Cubism, which was characterised by simplified surfaces and geometric forms.”

The outcome of taking abstraction and cubism to their extremes is Suprematism, which is primarily represented by the Russian and Soviet artist Kazimir Malevich. One of his works consisted of a black square, which he hung across the corner of a room in the same way as icons are hung in Russia.

“The cover of Unknown Pleasures is also a black square, which gives it a minimalistic and simplified aesthetic. At the same time, there are the white lines which create a pattern, which is vaguely figurative. They remind us of a mountain or something that we have previously seen, although they are totally inexplicable”, observes Wiik.

“Suprematism gave simple forms and empty surfaces a spiritual significance. In icons, the empty golden surfaces symbolise the divine. On this cover, the empty surface is black, which according to our cultural associations make us think of something depressing and frightening. It can be interpreted as an awe-inspiring experience of a great power, and thus the image becomes sublime – it is enjoyable and terrible at the same time.”

Johan Lindén is not particularly impressed by the curves used on the cover of Unknown Pleasures; he feels that there are aesthetically more attractive curves available.

“The pulses have been arranged in a row so that they form a 3D pattern reminiscent of a landscape. They should actually be identical. The variation in them may to some extent be explained by the signals being distorted as they travel through the atmosphere. Partly, this might be caused by the instruments used”, Lindén explains.

“Some measurement data do look attractive, but pulsar curves look like any other curves.”

When analysing why the album cover has, after all, become as iconic as it has, we must not forget the impact rock bands have on creating identities. They become something that their fans want to identify with, and the album cover is an image that can be used for ‘dressing’ oneself and one’s environment.

Wiik says that the theme of the cover is based on the industrial aspect of Joy Division’s music, which is characterised by rather monotonous rhythm and a synthetic sound under the desperate vocal tones of Ian Curtis.

“Modernity has a dark side to it. Joy Division’s aesthetic is also gothic, which leads us back to Romanticism and the melancholy mind. Romanticism also contained a lot of anxiety and focussed on emotions, not rationality.”

Joy Division

Joy Division was a rock band formed in 1976 in Manchester, England. The style of the band was a refined and a more artistic version of the raw energy of punk, paving the way for so-called ‘post-punk’. The career of the band was short-lived. Joy Division had themselves produced the EP An Ideal for Living (1978) before being discovered by the record company Factory Records, which released the album Unknown Pleasures in 1979.

An essential part of the myth of Joy Division is the vocalist Ian Curtis’s constant struggle with himself and his existence. Curtis committed suicide the evening before the band was due to start its first tour of the USA in May 1980. The album Closer was released posthumously in July 1980.

The rest of the Joy Division members – Bernard Sumner, Peter Hook and Stephen Morris – continued their career as the band New Order. The band has split up twice and replaced its members even more frequently, but has been playing actively again since 2011.