With work putting a bigger strain on the mind than on the body, the demand for cognitive fitness has increased. Meanwhile, the population is rapidly ageing and memory disorders are becoming more common. A new digital market promises easy solutions to reduce our worries, but does not seem to live up to the expectations.

Text: Nicklas Hägen

I HAD A memory training app in my mobile some time ago. Ironically enough, I can’t remember what kind of tasks it involved, but probably they weren’t interesting or rewarding enough, as I stopped using it after some time.

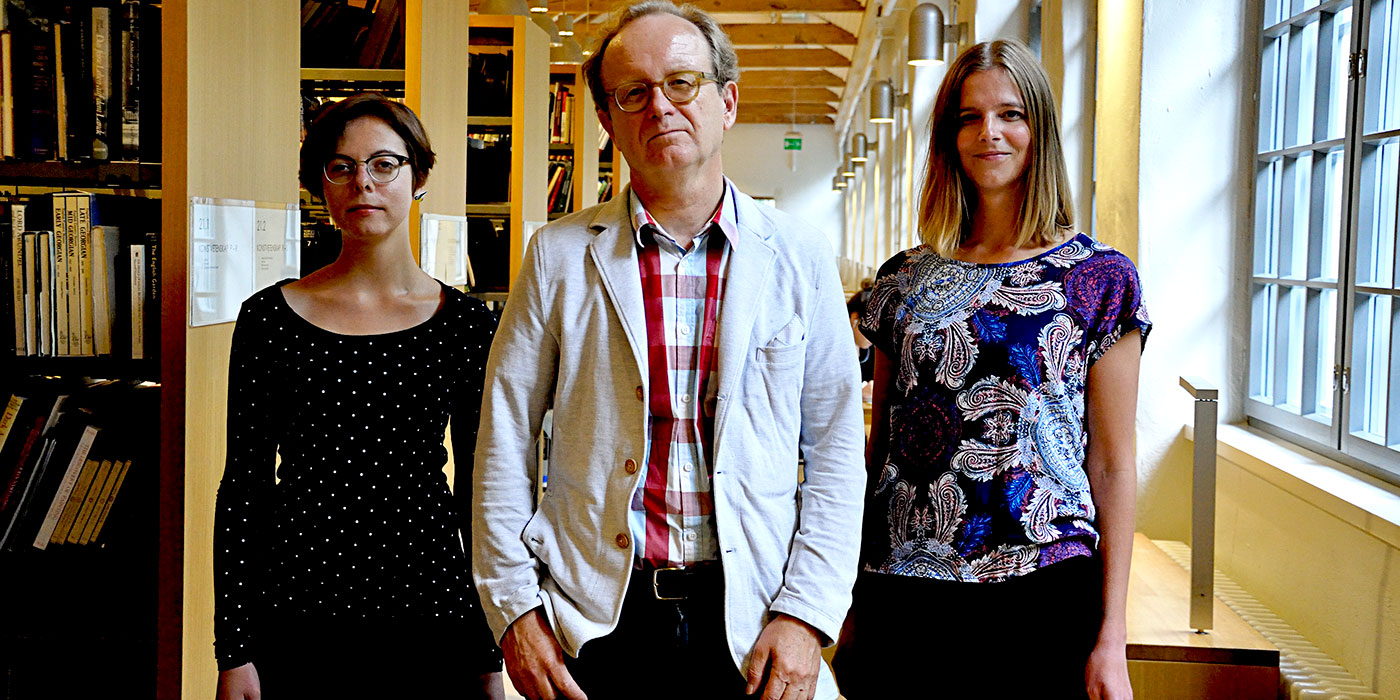

Just as well, according to Matti Laine, Professor of Psychology, and researcher Anna Soveri at Åbo Akademi University. Memory training is not likely to cure my absent-mindedness or improve my memory to any considerable degree.

“Training does not seem to offer any promising results. The meta-analysis we have done shows that there is a big difference between the groups that train and those who don’t train when it comes to the specific training tasks. Moreover, the training groups improve on untrained tasks that are very similar to the ones they trained on. But when looking at other assignments different from the training task, the effect is minuscule,” Soveri explains.

“If you perform the same tasks, but with other stimuli, there is an impact. For example, if you practise using numbers, you’re able to perform the same task using letters. But the effect is very limited. It does not transfer to a structurally different task, and it diminishes if you stop training.”

Laine refers to the expression ‘the curse of specificity’.

“Whichever skill you work at, you become better at that specific task, but not much more. If I practise playing the piano, I become better at playing the piano, but I don’t improve my skills in playing the violin,” Laine exemplifies.

Fast growth

Although there is no proof that memory training does improve one’s memory, the industry is growing fast. According to SharpBrains, a company specialising in market research of the so-called cognitive fitness market, the turnover of the industry has already reached over one billion dollars. The number of enterprises and apps within the field has increased explosively in the last years and the turnover is estimated to grow to six billion dollars within a few years.

The growing market has caused a larger need for consumer protection. In early 2016, the creator and marketer of the Lumosity memory training app, Lumos Labs, agreed with the US government authorities to pay two million dollars in compensation for false marketing. Their advertising claimed that the app would improve daily performance at work and school, and reduce or postpone a weakening of the cognitive functions caused by old age or serious illness.

“You can claim that your program is efficient and that you have a new way of implementing it. This might even be true. But the burden of proof is on you, and there are strict methodological requirements on the testing. They are similar to the principles of testing new medicines. Having just one group that uses your program for a few weeks, and interviewing them before and after doing so, does not suffice as proof that the program works,” says Laine.

Better effect on persons with memory disorders

The impact of memory training can be said to be negligible, but there are, nevertheless, exceptions. Patients diagnosed with various memory disorders seem to gain a more generalisable advantage from training than persons with an intact memory.

One reason for this might be that the efficiency of the executive functions, including working memory and concentration ability, follows a curve which peaks at around the age of twenty. And since test persons in the studies are usually university students, they are close to their highest potential; thus there is not much room for improvement, and the training might prove useless. However, when test persons are at a lower point on the curve and unable to use their full capacity, they might be able to compensate through training.

Another reason why patient groups might achieve better results through training can be that the training has a diffuse, generally positive effect, which is reflected in how they perform in tests.

“The tasks train many things other than just working memory. Therefore you might start performing better in a task, although it’s not your working memory capacity that has improved,” Soveri explains.

Laine adds that the various functions are not isolated entities. Working memory cannot be tested without the involvement of social (like the motivation to participate) or linguistic aspects.

“If the task is to repeat a sequence of numbers, you must concentrate on it. But if you’re doing it on a computer, you must also keep the test instructions in mind. After a while, you become faster at using the computer, more used to number sequences and start creating strategies for remembering,” says Laine.

“So perhaps it’s not the case that training of working memory influences the actual working memory, but rather that it’s mediated by other aspects – by taking your time, focussing on something and improving your computer skills.”

Effects, mechanisms and strategies

BrainTrain is a Centre of Excellence research project at Åbo Akademi, funded by the Åbo Akademi University Foundation since the beginning of 2015. The project will continue until the end of 2018.

The object is to explore working memory very extensively, for example using a web-based test platform, which makes it possible to test a significantly larger number of people and without geographical limitations.

“We will look at whether a link exists between several factors – health, hobbies, nutrition, sleep quality, stress level and linguistic background – and how well or badly the test persons do in the tasks. Do you have a better working memory if your level of education is higher, if you are not depressed, if you eat dark chocolate, drink red wine, eat nuts or exercise? Is there a connection?” asks Soveri.

So far the project has managed to find out how working memory is influenced by training; they have begun to be able to foresee how a certain kind of training might give results (although weak) and at what point the effect dwindles.

The strategies people use, for example, to divide long number sequences into groups, or to make up words of letter sequences have proved to be an important issue. When you have to keep things in mind for a short time, you can do it in various ways, and some are better for the purpose than others.

“People tend to make associations with a wide range of things, and these probably play an important role. There isn’t much written on this in literature, and this is one of the things we are going to study during the next two years,” says Laine.

The way in which the strategies work might explain why the effects of memory training are so limited.

“The test persons perhaps develop good strategies for performing tasks that they train three times a week for five weeks, but the strategy only works for a certain kind of assignments and not for others,” he continues.

“Usually when we give training tasks to test persons, we don’t provide them with instructions as to the best way of remembering things. People find out themselves, either consciously or unconsciously, how they can best manage their tasks. We have tried to interview people about how they do that, but their descriptions are not all that detailed. This is something we want to explore in more depth.”

What does the test test?

When the BrainTrain researchers started digging into literature in the field, they found that there was surprisingly little methodological research into whether working memory tests and other executive measures actually measure what they are believed to measure. Nor is there a consensus as to the best way of using tests; different studies use different tests and combine them in different ways.

BrainTrain is conducting a meta-analysis in order to explore what popular executive tests measure, by analysing how the various ways of measuring the executive functions correlate to each other. The long-term goal is to develop a tests that are closer to everyday life.

“Researchers and clinicians look at what happens in the brain when a person performs a task that is supposed to measure working memory. They can see that certain areas are activated, but if the task doesn’t specifically measure working memory, the entire description is incorrect. In that case, the way in which the tasks are used must be changed,” says Soveri.

“Perhaps the tasks are chosen without any further reflection. They are simply chosen since they are assumed to measure working memory, but the test has never been monitored as to its actual function. We’re going back to the roots here.”

That sounds as if it might have a dramatic impact on the research results?

“We must bear in mind that working memory is not an empty theoretical concept without any significance. It’s obvious that the tests that we criticise do quite strongly correlate with other things in real life, such as academic performance or, in the case of children, how well they learn foreign languages or how well they can control their emotions,” Laine says.

“Working memory is not just about cold data processing, it’s also affected by emotions and motivation. It’s important that it is linked to real life and therefore we need to learn more about the building blocks of working memory. We don’t know what the natural components of the brain and the mind are, how they function and do various things. It’s a matter of, to quote Plato, ‘carve nature at its joints’.”

Is there any hope for those with a poor memory?

“Perhaps to use better strategies in various contexts. But there is no patent solution in sight,” Laine says.

“It is more a matter of a healthy lifestyle,” Soveri adds.

“Go out jogging, eat relatively well, sleep enough and be social. That’s quite a good recipe. The advice we have for a healthy lifestyle also supports your memory,” Laine concludes.

The question as to what happens when we remember things makes researchers sigh deeply. There is no easy answer to how memory should be described.

“Something happens in the brain, there’s no doubt about that. Working memory seems to be about an increased level of activity in the brain’s network, that is why it is temporary. When moving to long-term memory, we’re talking about a different system, structural changes based on the activity in certain loops and networks. Over time, these create structural changes in your synapses, which are the contacts between nerve cells. This lays the foundation for long-term memory. Even if you focus on other things in between, you can return to these things,” says Matti Laine, Professor of Psychology at Åbo Akademi University.

Working memory was called short-term memory until the 1970s. The new term reflected a wish to emphasize the active part of working memory, the fact that it’s something happening here and now.

“Working memory can be regarded as a part separate from long-term memory. But there is also another view, which considers them to be one system where working memory constitutes the active part of long-term memory,” Laine explains.

“In that case your working memory could be described as a large library where you go with a torch and see different things at different times. Working memory can be seen as a mental platform moving according to what you’re doing at the moment, and its contents can originate partly in long-term memory, partly in external factors.”

A typical working memory test consists of repeating number sequences, perhaps also manipulating them by repeating them backwards. In functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) this mainly shows response at the front of the brain.

“Repeating number sequences is a verbal task, which activates the left hemisphere, mainly the left frontal lobe, the left parietal lobe and the auditory cerebral cortex. If you’re given visual input through the computer screen, the visual cortex is also activated, and possibly other areas related to language,” Laine says.

The difficulty is that fMRI measures on a very broad scale.

“With fMRI we measure widely, and then have to relate the specific objective of the measurement to other things happening, in this case working memory in relation to social and linguistic factors. It’s difficult to tell whether the response is created by working memory specifically. Perhaps the working memory operations take place in the cortical columns? They are extremely small and most likely to display interesting patterns, but we cannot make non-invasive measurements at sub-millimetre level.”

Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation, tDCS, is a form of non-invasive brain stimulation. Two electrodes are placed on top of a person’s head and a weak electric voltage is created between them.

In theory, tDCS is supposed to create better conditions for learning and improved cognitive performance. This is because activity in the brain is based on nerve signals consisting of electric impulses. By increasing their effect, the aim is to create structural changes in the brain, which will result in the rebuilding of synapses, that is, the contact points between nerve cells.

“Brain cells communicate with each other through electrochemical signals that transmit information, but do so only if the tension exceeds a certain threshold. With this gadget, the threshold can be somewhat lower, which makes it easier for the cells to create communication channels between them,” says Karolina Lukasik, post-graduate student in psychology at Åbo Akademi.

“We have placed the electrodes on parts of the brain that are particularly active with regard to verbal working memory. The participants perform a working memory task and we hope that they will perform better when receiving stimulation. So far, we have only done pilot testing, so we cannot say very much about the results yet.”

This technique is new, so it is still unclear how great an impact it actually has and what the best way to use it is. The advantage is that tDCS is very easy to use and does not require a large lab.

“The technique is also safe, there are no reports of negative long-term effects. Users say that they get red marks on their skin from the heat emanating from the electrodes, occasionally they get headaches or experience a tickling sensation. On the other hand, test participants cannot say whether they have received actual stimulation or placebo, so it’s obvious that the expectations of something happening are great,” says Lukasik.

There are inexpensive tDCS devices available for ordinary consumers. But, as with all technology for memory training, it is recommended not to expect too much in the way of results.

“People want easy fixes, an easy way to improve. However, research indicates that there is no easy way of improving memory, apart from a healthy diet, lifestyle and hobbies. You can buy all the tDCS devices in the world, but if that is the only thing you do, it is unlikely to work.”