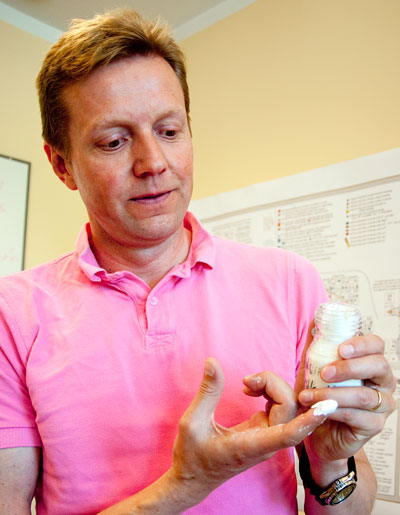

Peter Österholm. Photo: Nicklas Hägen.

Acid sulphate soils contain high quantities of sulphate compounds and are very fertile. However, when these soils are turned by dredging or ditching, processes are started that might have considerable negative environmental impacts, including massive fish die-offs.

There is a large proportion of sulphate in seawater, and sulphates are a natural part of the environment. However, when acidic sulphate soil comes into contact with oxygen, the sulphates and minerals in the soil combine to provide all the ingredients needed for creating sulphuric acid and solutions high in heavy metals. These, in turn, constitute a severe problem.

Peter Österholm, a lecturer in geology at Åbo Akademi University, is chair of an international working group focussing on acid sulphate soils.

“In Finland, acid sulphate soil is an environmental problem, but there are many places in the world where it could be described as an issue of life and death – there are particularly sensitive environments in which cultivating the land in the wrong way might cause conditions that totally destroy opportunities for farming or fishing,” says Österholm.

Research into acid sulphate soils has been carried out at Åbo Akademi University since the 1990s. One area has been to develop methods for identifying so-called potentially acid sulphate soils, that is, soils that will turn acid if oxidation processes start.

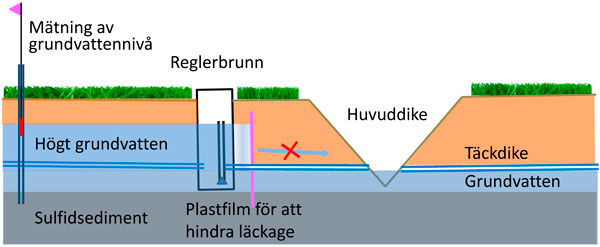

In collaboration with farmers, Österholm and his colleagues have also worked on methods for minimising the damage caused by cultivation. One method that has provided positive results and is being developed further is so-called regulated drainage, where the outflow from a field’s covered drains can be regulated. If water is available, it is also relatively easy to pump extra water into the system in order to reduce the level of oxidation.

It is harmful to drain too much – each drained decimetre corresponds to the impact of one year’s acid rain, and in the summer the plants often suffer from drought. This can be avoided by regulated drainage.

“When the desired depth is achieved, it’s possible to store water for the summer. This gives the landowners a better water balance, and it’s a good means of protection against drought if climate change leads to drier summers here,” says Österholm.

A project called Chemical Precision Treatment of Acid Sulphate Soils, PRECIKEM, has also developed a new method where irrigation pumps are used for pumping neutralising lime into acid sulphate soils. The application of just a moderate dose has been proved to considerably reduce the concentration of aluminium. Currently the long-term effects are being investigated.

“When spreading lime from above, everything remains on the surface and does not reach down to the critical acid soil layers deeper in the ground. If the lime is pumped through the system in which water normally runs, the treatment reaches the hydrologically active pores, which are of key importance. The problem has been to find lime that does not clog the pores, but we have achieved good results with the finest grade of lime obtained from the Nordkalk Corporation.”

Regulated drainage

To the left of the ditch: Regulation of the outflow from covered drains using a regulating well and a ‘floating groundwater antenna’ for easy monitoring of the groundwater level. If regulation is started early enough in the spring, the sinking of the groundwater level can be slowed down. To the right: A conventional covered drain without regulation. Recreated from Österholm & Rosendahl 2012.